The Fed reached its inflation target years ago. It just never noticed. Part 1.

Part 1. Neither inflation nor deflation is what it seems

First published: November 2021. Last update: Feb 2022

This study is a compilation of my articles published in online financial journals Portfolio and ConcordeBlog during 2020-2021.

-------

As a result of misinterpretations of inflation and deflation, central banks rely on false signals and make wrong decisions. In recent years, they failed to recognize inflation and remained way too expansionary way too long. Earlier, they saw inflation where there was not, and exacerbated recessions by unjustified tightening. The correct interpretation of price changes and the localization of surplus money would lead us to better monetary policy decisions.

-------

Neither inflation nor deflation is what it seems

Introduction and summary

In the 2010s, misinterpretation of inflation and deflation led to the Fed

erroneously identifying the impacts of globalization, innovation, and tax cuts as the deflation of money (which they are not),

ignoring, even contributing to, severe inflation in certain consumer goods markets (due to not noticing that actual inflation is only counterbalanced in the CPI by the non-monetary impacts of globalization, innovation, and tax cuts),

ignoring, even contributing to, severe inflation in asset prices (for only focusing on the consumer basket and not noticing that the consequences of the inflation of a currency may also show up elsewhere in the economy).

As a consequence, the Fed did not notice the massive overshooting of its inflation target already years ago, remained unnecessarily expansionary for years, and caused severe economic and financial markets distortions.

Earlier, in the 1970s, the misinterpretation of inflation led to the Fed erroneously identifying the price impacts of an oil embargo as the inflation of money (which it was not). As a consequence, the Fed severely tightened monetary conditions, and stifled an economy already heavily suffering from high oil prices and CPI-indexed wages.

There are identifiable roots of the above misinterpretations, as well as potential solutions that are presented below.

Key assumptions and definitions used in this study

The primary role of central banks

The utmost important responsibility of central banks is to have exactly as much money in the economy as the economy requires for a healthy functioning. By ensuring that the supply of money equals the demand for money, the central bank maintains a stable value of the currency.

Money creation

Increasing the total amount of money in the economy by the banking system primarily through lending.

Money printing

The creation of excess money, money that exceeds the needs of the economy.

Inflation

The depreciation of money and the resulting rise in prices of any kind of goods, products or assets (as opposed to a general increase in prices of consumer goods).

Deflation

The appreciation of money and the resulting decline in prices (as opposed to a decline of prices of consumer goods).

Key statements of the study

Today's discourse of economics identifies inflation as rising consumer prices, and identifies deflation as declining consumer prices. Both definitions are wrong.

Consumer prices rising is often not a consequence or sign of the inflation of a currency. Bad weather or climate change, insufficient investments or supply chain bottlenecks lead to goods getting pricier without money losing its value. You pay more for higher value.

Similarly, declining consumer prices is often not a sign of the deflation of money. Technology is not deflationary. Innovation lowers prices without the appreciation of money. You pay less for products that have become easier to produce.

Inflation does not necessarily reveal itself in consumer prices. If all excess money ends up in the stock market, you’ll see true, real, actual inflation there.

Inflation does not necessarily reveal itself in a general increase in consumer goods prices. If all excess money only ends up in education or healthcare, you have to fight inflation there.

As a consequence, widely followed price indices, CPI, core CPI, PCE or any other price indices, only have very limited relevance and use in measuring the actual inflation or deflation of a currency. They are best understood as symptoms of potentially very diverse causes.

As central banks seek to respond to inflation or deflation in their key decisions, the above misunderstandings have serious consequences.

Driven by inflation fears, central banks also tighten in unjustified cases, downing economies already weakened by higher prices - be it due to climate change, tax or tariff increases, oil embargos, lack of wood, coal, copper, or chips.

At the same time, however, they do not stop the expansion of money supply despite the clear and staggering depreciation of money in cases such as the asset price inflation of the last 10 years.

Today, at the end of 2021, halting widespread price increases is in the crosshairs. A recession generated by harsh central bank tightening would probably stop prices, but the correct interpretation of price changes, the precise localization of surplus money and targeted intervention would likely lead us to an outcome that is better than a recession.

Inflation

Prices rising is not necessarily inflation

Today's discourse of economics identifies inflation as rising consumer prices. It sees inflation as if any price change measured by the CPI would be monetary phenomena, as if every price increase would be due to the depreciation of money. But this is not the case.

A hundred years ago, economic literature was still familiar with the different phenomena of goods getting pricier and inflation. Inflation was considered the consequence of a superfluous amount of money, i.e. the depreciation of money, while the root causes of goods getting pricier were sought in the real economy. Similarly, below, I only refer to inflation as the depreciation of money, which I sharply distinguish from price changes for reasons beyond the control of money or monetary policy.

Goods getting pricier (you may also call it goods getting dearer), for example, is

when whisky is expensive because of prohibition,

when cherries are expensive because of spring frost,

when oil is expensive because of Persian Gulf crises,

when flowers are expensive on Mother's Day,

when on New Year's Eve everything is expensive from airfare to hotels, from restaurants to taxis.

In these situations, it is not money that loses its value, but it is the value of certain products or services that increases - temporarily or permanently - and money, as an excellent value-measuring instrument, shows us the growth in their value. In such situations, prices would soar even if measured in gold (or in any other non-inflatable currency).

When I say services I also mean all forms of work. When wage increases reflect growth in the value of labor, it shall not be called wage inflation. It shall be called proper wages.

It is customary to say in the above situations that the purchasing power of money decreases as less products are available for purchase from the same amount of money as a result of goods becoming pricier. But this statement is incorrect. Actually, the purchasing power of money does not change in the above situations. What happens is that we pay a higher price for a higher value.

Since these are not monetary phenomena, the central bank has nothing to do with them, it does not even have the means to deal with them, and despite the rising prices, it is not justifiable for the central bank to tighten and reduce money supply.

The central bank has an indirect responsibility, that is, to make it clear through regular and firm communication that it is not the depreciation of money that is behind price increases, and thus keep inflation expectations in check.

The issue of “imported inflation”

The current discourse of economics considers inflation “imported” when imported goods become pricier due to a weaker currency. (Some economists define “imported inflation” more broadly.)

But if you only deem inflation the depreciation of money, then inflation is almost never imported. In most cases, a weaker currency is the consequence of either

domestic inflation that results in both domestic and import prices increasing, or

the deteriorating competitiveness of an economy that results in imported goods becoming relatively more valuable, i.e. more expensive, as transpired by the weaker exchange rate.

In the case of a deteriorating competitiveness of an economy, efforts by the central bank to prevent the deterioration of the exchange rate and to prevent “imported inflation”, especially if stabilization is intended via higher rates, will lead to an unstable (artificially strong) currency, the poor performance of the economy remaining disguised and economic agents taking extraordinary risks by seeking financing at lower rates in foreign currencies.

It shall be noted that under special circumstances, excess money and/or inflation can be “imported”, e.g. by excess money crossing currency borders (money printed in one country and spent in another, or even money printed in the crypto world and spent in the fiat world).

The issue of quality-adjusted prices

Although not directly related to the above, it is worth mentioning that since consumer price indices are calculated at constant product quality, price increases associated with quality improvements will not induce a higher index. As a consequence, the price increases perceived by consumers may be significantly greater than the increase in the CPI in situations where the products available in stores are widely replaced to higher quality products (while older, lower quality and cheaper products become unavailable).

There are notable examples of such price changes in many sectors in recent years. While such price increases shall not be called inflation and it is right that they do not show up in price indices, they still may lead to a significant increase in consumer expenditures and, if unexplained, lead to dissatisfaction with monetary policy.

Inflation also exists outside of consumer price indices

As today's discourse of economics identifies inflation as rising consumer prices, it does not consider price increases that occur outside of the consumer goods market to be inflation. If the central bank or commercial banks flood the world with excess money, but the excess money all ends up in the stock market, almost no one realizes that there’s a problem, as stocks are not in the basket of consumer goods.

But there’s only one US dollar, and if excess dollars get into the economic and financial system, the dollar will lose some of its value, you just have to notice where. Experts often refer to asset price inflation as if it were not exactly the same inflation that occurs in consumer goods markets, when in fact it is exactly the same.

One of the main drivers of bond and stock market price increases over the past 10-20 years has been true, real, actual inflation.

Inflation

In my interpretation inflation is only the depreciation of money and the resulting rise in prices, which may occur in any part of the economy. (As opposed to the current, widespread definition of a general increase in prices of consumer goods, and also as opposed to the original definition deriving from the early 20th century, that is any increase in the supply of money.)

The cause of real inflation can be twofold:

the creation of excess money, i.e. money printing, which in our modern credit money systems primarily means surplus, unjustified loans by either commercial banks or the central bank (it may also derive from mispriced purchases of foreign currency),

or the self-fulfillment of inflation expectations of economic agents, even if completely unfounded.

Money printing

In a healthy, modern banking system the amount of money in circulation is determined by the money demand of the economy. In a growing economy, more and more money is needed by economic agents to conduct all their business transactions, while in a shrinking economy, less money is necessary. Cash-based economies need more money to be in circulation, while digital payments based economies need less. Societies that hoard cash in pillowcases need more than societies that save money in bank deposits. An economy that is frightened of a crisis and is frozen and fleeing into cash needs more money than an economy running smoothly.

Normally, the increasing money demand of the economy is satisfied by commercial banks by providing more loans, while in the case of money demand decreasing, the amount of money that becomes redundant is withdrawn from circulation by economic agents repaying their loans.

In modern credit money systems, ‘money creation’ is when the banking system - primarily commercial banks, in special situations also the central bank - increases the total amount of money in the economy through lending (or through the purchase of foreign currency). Whereas ‘money printing’ is the creation of excess money, that is, when the banking system, consciously or not, injects more money into the economic cycle than the economy needs.

In other words, money printing is unjustifiable, uncareful or irresponsible bank lending.

Money printing, however, is not as easy to recognize or expose as we might think. The inflation of central bank balance sheets, which many identify with money printing, does not in itself necessarily mean that excess, or even any money entered the economy. The reason is, on the one hand, that there is no direct relationship between the central bank's balance sheet and total money supply, and on the other hand, that no excess money is printed when increased money supply serves an increased money demand of the economy. Moreover, in modern banking systems, 90 percent of money supply is controlled by the lending activity of commercial banks and not by the balance sheet of central banks.

Accordingly, similar to price indices that only have very limited relevance in measuring inflation, monetary aggregates also are of very limited utility without a proper understanding of all the factors driving money demand.

Inflation expectations

It is not just money printing that leads to inflation. The depreciation of money, i.e. inflation, may also materialize when a wide range of economic agents, whether justified or unjustified, for fear of the devaluation of money, increase prices and thus essentially meet their own expectations. In such situations, it is not money printing, but widespread fear that leads to a loss of faith in the currency, therefore to inflation.

Accordingly, managing inflation expectations, i.e. maintaining faith in the value of their currency, is of paramount importance for central banks. As described above, proper management of expectations assumes and also requires the correct interpretation of price changes.

Unfortunately, however, central banks themselves might also generate inflation expectations when they call inflation such price increases that clearly do not derive from a loss of value of money. A recent example is ‘temporary or transitory inflation’ an expression widely used to refer to price increases due to supply shortages during the current global pandemic. In such situations, the term ‘temporary inflation’ is both erroneous and dangerous, playing with fire, and undermining the credibility of the central bank and its currency. Such price increases might be temporary, but they’re definitely not inflation.

The term ‘transitory inflation’ suggests that the central bank consciously lets its currency loose some of its value because it is confident of its temporary nature. However, price increases due to supply shortages during a pandemic - or other similar events - are not monetary phenomena, central banks or the banking system bear no responsibility for them, actually they can hardly do anything to guard against them. What they can and shall do, however, is not call these price changes inflation.

The trickiest of all are the slow, but lasting changes in economic circumstances (like climate change) that inescapably lead to goods becoming pricier. We also tend to call their price impacts “transitory inflation”, though they’re neither transitory, nor inflation. Higher prices due to more demanding weather conditions, and the intensifying battle for oxygen, water and soil are absolutely not monetary phenomena, central banks have no means to fight them. Cleaner and greener products, scarce natural resources will be of higher value - and price. Greenflation is not inflation.

Unfortunately, we are about to see additional, significant, non-inflationary price increases in the coming years due to green policies, aging, international conflicts, tax increases and several other factors. They might turn low CPI targets unrealistic for quite a while.

Managing inflation and inflation expectations

In modern credit money systems, to keep inflation under control,

there shall be exactly as much money in circulation as the economy needs to carry out its economic and financial transactions,

but equally importantly the central bank shall sustain faith in the value of its currency by actively managing inflation expectations.

Although money demand is not easy to measure and inflation expectations are not easy to control, proper interpretation of inflation is definitely a necessary starting point for both.

In order to find the balance of money supply and demand, it is essential that the central bank

recognizes and stops markedly uncareful bank lending, including central bank lending, and

recognizes and differentiates between price increases that are justified by economic developments (goods becoming pricier) and price increases that result from the depreciation of money (inflation).

Deflation

Deflation

While inflation is the depreciation of money, deflation is the appreciation of money due to insufficient money, and the decline in prices as a result of the appreciation.

Deflation can be caused by either an overly restrictive monetary policy, a sudden slowdown in the velocity of money, an inflexible banking system, or a rapid outflow of capital from a country.

Deflation is considered harmful by financial economics because

insufficient money slows down economic processes,

money appreciation increases the value of debt and makes it more difficult to repay, it also increases the real interest burden on loans,

asymmetrically flexible prices and wages (they are more difficult to reduce) make it difficult for the economy to adapt to deflation,

falling prices force economic agents to postpone purchase and investment decisions.

Altogether, they may lead to a deflationary spiral, a decline in consumption and investment, and a sharp slowdown in the economy.

Understandably, therefore, seeing signs of deflation, central banks try to expand money supply vigorously until the horror of unbridled inflation appears, to which the central bank then responds by narrowing money supply until the horror of unstoppable deflation, and so on, and so on, and so on…, goes on an alternating expansion and tightening and the search for a sustainable balance. And in recent decades, sustainable balance has been announced and targeted, I believe correctly, by monetary policymakers globally at moderate, 1-3 percent inflation.

Prices falling is not necessarily deflation

However, just as inflation cannot always be identified with rising consumer prices, deflation is also not simply a fall in consumer prices.

In fact, it is not deflation, because it is not a change in the value of money when

agricultural products become cheaper due to favorable weather,

prices fall due to tax cuts,

engineering or business innovations improve efficiency, and lead to price declines,

or when price declines are the fruits of global trade and production systems (in essence also better efficiency).

These are not monetary phenomena, they are not induced by insufficient money or the change in the value of money, and therefore they shall not be called deflation. What happens in the above cases is that favorable weather, innovation and globalization reduce the value of products (as it becomes easier to produce or procure them), and money as an excellent value-measuring instrument shows us this in the form of lower prices. (While lower taxes are actually income transfers that also have nothing to do with the value of money.)

Technology is deflationary - the saying goes. But it’s not. Technology does not change the value of money. It changes our standard of living.

Since these are not monetary phenomena, the central bank has nothing to do with them, it does not even have the means to deal with them, and despite falling prices, it is not justifiable for the central bank to ease monetary policy, cut interest rates or keep interest rates low, and increase money supply.

The central bank has an indirect responsibility, that is to make it clear through regular and firm communication that it is not the lack of money that is behind price cuts, and thus keep deflation expectations in check.

The consequences of misinterpretation

Inflation targeting strategies rely on false signals

Major central banks globally maintain inflation targeting strategies with rather less than more success. This should come as no surprise since these are actually consumer price index targeting strategies, which only could be successful if central banks could control alcohol bans, spring frosts, Persian Gulf conflicts and oil cartels, tax and tariff changes, chip production, wood processing, Mother's Day and New Year's Eve, as well as changes in productivity, innovation and consumer habits. But they certainly can’t.

The end result: due to a superficial interpretation of inflation and deflation, inflation targeting strategies rely on false signals, and central banks try to make right decisions based on these false signals. It is a hopeless hassle, and leads to a great deal of difficulties.

Unjustified tightening

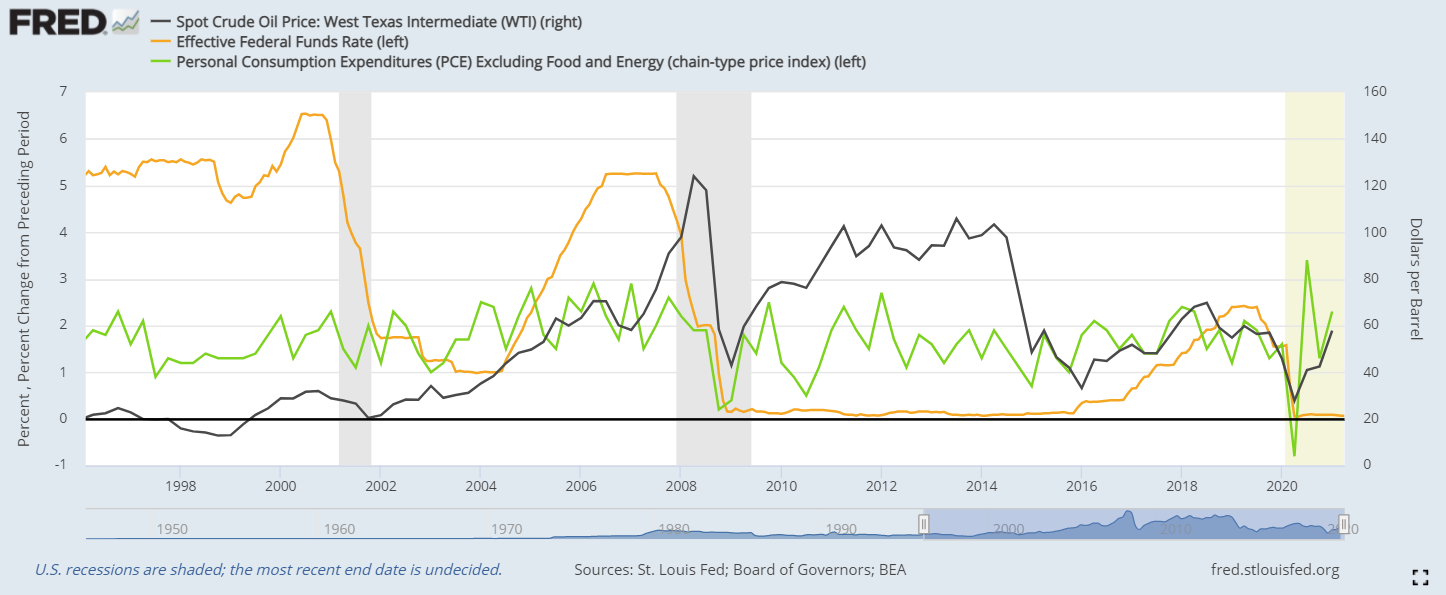

In recent decades, for example, the Fed has always responded to rising oil prices, no matter what the root cause was, by tightening (e.g. cartel and war in the 1970s, recovery from the Russian crisis in 1999-2000, supply difficulties in the mid-2000s), and made the prospects of the economy, which already was grim due to higher oil prices even bleaker. It led to some serious trouble in the 70s, in 2000-2001, and also in 2007-2008 (caused also by other, non-negligible factors, of course). Even in 2015, the monetary tightening cycle started hand in hand with the rise in oil prices, and in 2018 it stopped when oil prices started to fall.

PCE (%, lhs), oil price (USD, rhs) and Fed funds rate (%, lhs)

(Shaded areas indicate recessions.) Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

The mistaken monetary policy of the 1970s

The two oil crises of the 1970s and their aftermath, including multi-year stagflation are particularly exciting in this regard. Stagflation, economic stagnation and rising prices are expected by many today to recur due to the recent commodity price explosion and expected central bank tightening.

What happened back then was shaped by several factors (including the end of dollar to gold convertibility, wage and price freezes, budget deficits), but it can be simplified to the following: due the OAPEC oil embargo in 73 and the Iran crisis in 79 oil has become several times more expensive in a few months, resulting in significant cost increases in almost every sector of a heavily oil-dependent US economy and through cost pass-through, weighty price increases and a sharp upturn in the CPI.

Though it was called inflation, the rise in oil prices was not inflation, since it was not money that lost its value rather it was oil that appreciated.

The rise in oil prices made everything more expensive.

(Shaded areas indicate recessions.) Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

The situation was exacerbated by the fact that a significant part of employment contracts were tied to the CPI through wage indexation, meaning that the explosion in oil prices led to essentially automatic wage increases. These were, in fact, unjustified wage increases not justified by the depreciation of money nor by better performance of employees or companies, not even by labor shortages. The main misconception was that CPI and inflation are the same and that inflation deserves an automatic wage increase. Not surprisingly, in addition to the price of oil, higher wages have further raised the costs and the price of goods and services, i.e. the CPI.

Companies thus were already struggling with two extra burdens: the unexpected, sudden and sharp rise in oil prices and unjustified and significant wage increases. These in themselves would have probably led to stagnation or even recession but that’s when the central bank intervened. Interpreting the sharp rise in the CPI as inflation, the Fed responded with strong monetary tightening and essentially stifled an already heavily suffering economy.

The Fed finally stopped the rise in prices - by knocking the economy to the ground.

What could have been done? In response to the severe shock to the economy, instead of monetary tightening, a selective and targeted easing, a modification or termination of wage indexing agreements, as well as a much more proficient and circumspect management of inflation expectations would have been the right measures.

The Fed should have protected faith in the value of the dollar. They should have made economic agents understand that the high price of oil is not a sign of the depreciation of the dollar, but the sign of an increase in the value of oil, which the dollar, an excellent and stable measure of value, insensitively confronts us with. The Fed should have made it clear that the problem could not be remedied by monetary means, but by transforming oil production, oil trade and an oil-based economy.

Unjustified easing

The last two decades, however, have been primarily not about monetary tightening but about easing.

Although not results of academic analysis, the charts below strongly suggest that globalization, innovation, and tax cuts have had a strong downward impact on prices over the past 10 to 20 years, contributing to low consumer price indices that remained below the Fed’s target level and made the Fed pursue a persistently extremely expansionary monetary policy for fear of deflation. Unfortunately, unjustifiably.

Innovation and globalization are driving down consumer prices (red: hardware and IT services).

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Corporate income taxes have been falling worldwide for decades. Source: OECD

Personal income taxes, social security and employer contributions

are on a declining trend worldwide. Source: OECD

Globalization, innovation, and tax cuts driving down prices is not monetary phenomena. The resulting lower prices have not been induced by insufficient money or the change in the value of money, and therefore should not have been considered deflation. Unfortunately, their non-monetary price impacts kept general price indices low and made actual, severe inflation in certain consumer goods markets invisible.

I believe, the Fed has reacted improperly to low consumer price indices over the past decade, fearing deflation unduly, and pursuing an unjustifiably expansionary monetary policy in order to reach its target 2 percent CPI, and as a consequence it has allowed excess money to flood the markets and the economy.

Consequences in 2021

Although there have been occasions of unjustifiably harsh interest rate hikes in the past, this time, over the last 10 years, misunderstood inflation and deflation have led to the creation of excess money, i.e. to money printing.

And excess money

on the one hand, has been steadily and spectacularly inflating asset prices (bond, stock and property prices) for many years,

on the other hand, also led to significant, stealth inflation in certain areas of consumer goods - a wide range of services, health care, education - which was not transparent in consumer price indices only due to the price-reducing impacts of products that became cheaper due to non-monetary factors.

Money printing has led to a very unhealthy system of financial incentives with extremely cheap loans and zero (some parts of the world even negative) bond yields, as well as to asset price inflation and unrecognized consumer price inflation that have widened the social wealth and living standards gap.

Responsibilities of central banks

In defense of central banks

It should be noted that central banks not only follow just one consumer prices index, but several different indices, and also analyze price changes in many ways. But the point always remains ignored. Price changes resulting from the depreciation of money are never distinguished from price changes independent of the change in the value of money.

In defense of central banks, we also need to know that their task is difficult on two fronts. On the one hand, there is no easily manageable, objective measure of the money demand of the economy, i.e. how much money needs to be created, where the right level of interest rates is, what the actual real level of inflation is, what the right exchange rate is to foreign currencies. They can only be estimated, it is impossible to determine any of them precisely.

Furthermore, the primary legal obligation of central banks, maintaining price stability, is measured by consumer price indices and the exchange rate, despite none of them being necessarily the right measure of price stability. The consumer price index is misleading in the measurement of both inflation and deflation, while history has proven many times over that an unchanged exchange rate does not necessarily signal stability, and can even be very unstable depending primarily on changes in relative productivity.

On the other hand, central banks are in a difficult position because they also have legal obligations that they can hardly have a meaningful impact on. The Fed’s such legal obligation is the support of maximum employment in the economy.

Just the right amount of money in every market and sector

The utmost important task of central banks is to have exactly as much money in the economy as the economy needs for its healthy functioning. In modern credit money systems, the key to this is for banks to lend actively, flexibly and responsibly: provide funding for all credible business purposes but avoid funding hoaxes or quackery. The responsibility of central banks is to ensure this through regulation, incentives and restrictions, supervision, active and clear communication and sometimes direct market interventions.

If the right amount of money is in circulation money will not inflate. In order to avoid or curb inflation the central bank must, first of all, find and seize excess and uncareful loans. If there’s a flood of bad consumer mortgages, they intervene there, if leveraged trading positions reach a highly risky level, they change the rules there, if the BNPL market flames up, they intervene there, if it’s the government that is becoming heavily indebted to banks, that’s where you need tightening. It is the duty of the central bank to recognize where excess money is created or where excess money is flowing to, and they shall tighten conditions there.

To find the right decisions, monetary policy makers need to form an opinion on:

which price increases (including the price of labor, wages) stem from excess money, and which have non-monetary roots, e.g. economic structural difficulties, tax increases, value changes,

where there is excess money in certain markets or industries, how to eliminate it with targeted measures,

which price drops stem from a shortage of money, and which have non-monetary roots,

where a lack of money slows down economic processes, what targeted incentives could generate additional funding.

Over the past decades, central banks have made great strides in diversifying their monetary policy tools and better targeting their actions and interventions. Today’s monetary challenges also require tailor-made and targeted solutions.

-------

End of Part 1. To be continued.